William D Drake – The Rising Of The Lights out May 16th

I am delighted to announce that Bill’s new album will be out on 16th May. It will be available on vinyl LP (with insert), CD (with 12 page booklet) and MP3 download.

Distribution is being handled by Cargo so you should have no problem getting hold of it from record shops, Amazon, iTunes and all the other usual places.

You can hear the whole album streaming here for you to try before, hopefully, you buy.

Tracklisting:

Super Altar

Ant Trees

In An Ideal World

The Mastodon

Ornamental Hermit

Wholly Holey

The Rising Of The Lights

Song In The Key Of Concrete

Me Fish Bring

Ziegler

Laburnum

Homesweet Homestead Hideaway

Alongside Mr Drake the album features the distinguished talents of James Larcombe, Dug Parker, Nicola Baigent, Gaz Williams, Sion Organ and sublime special guest appearances from Bernie Holden, Richard Larcombe, Sarah Jones, Mark Cawthra, Frank Naughton and Jason Jervis.

There will be a series of concert performances in the summer to celebrate the release of the album. Dates so far confirmed are Arnolds, London, 17th May and The Komedia, Brighton, 17th June.

Thank you for your support and please feel free to spread the word.

Reviews

The Quietus

When reviewing the new album by an artist with a lengthy, if under-exposed, body of work behind them, it’s not always helpful to start by banging on about what they were doing thirty-odd years ago. In this case however, it seems relevant. William D Drake was once a member of Cardiacs, having been co-opted into the band by leader Tim Smith in 1983, shortly after the release of their debut album. Over the next decade – until his departure in 1992 – Drake was to become arguably the second most important contributor to Cardiacs music after Smith himself, his songwriting and his prodigious skills as a pianist and arranger helping to define the Cardiacs sound – complex, eccentric, absurdist, indebted to prog, psychedelia and whimsical English art-rock when such behaviour was far from fashionable – during their high-water years of the mid-to-late eighties.

During that time Cardiacs seemed like the ultimate cult band; attracting a large and loyal following, yet rarely mentioned in the music press of the day, and then only in terms of patronising disparagement. Their mix of surrealism, theatricality and complex, challenging musical constructions probably turned ten people against them for every one who swore allegiance for life. But, by the mid-nineties, bands like Blur and Supergrass had smoothed the considerable rough edges off the band’s trademark sound and had managed to turn it into commercial mainstream pop – something Blur at least acknowledged when they invited Cardiacs to support them at Mile End Stadium in 1995.

By then of course, Bill Drake was gone, to spend the nineties wending his way through a curious collection of unsung outfits, many featuring old Cardiacs colleagues. He continued to make guest appearances with the band, and remained one third of the Sea Nymphs, AKA Mr and Mrs Smith and Mr Drake. And it was Tim Smith who convinced him to record and release his first, self-titled solo album, a collection of stirring, beautiful-sad piano songs, in 2003. After spending the intervening years as a member of North Sea Radio Orchestra (with whom he still performs), 2007 saw not one, but two follow-ups: Briny Hooves added greater use of orchestration and band arrangements to Drake’s songs, while Yew’s Paw was an assured collection of classical piano instrumental pieces. Even those who were never drawn towards Cardiacs’ frenetic brand of prog-punk couldn’t fail to be impressed by the stately grandeur of Drake’s mature work.

So why dredge up the past now? Two reasons. One is that over the past year or so, Cardiacs’ reputation seems to be undergoing a reappraisal, with statements about how wonderful and influential they were erupting with increasing regularity in the mainstream press like geysers. The sad thing is that this reassessment has happened in the wake of Tim Smith’s debilitating heart attack and two consecutive strokes in the summer of 2008, which left him largely paralysed and unable to speak. At the end of last year a fund-raising tribute album on Believers Roast, Leader of the Starry Skies, raised the band’s profile still further. Needless to say, William D Drake was among the contributors.

Second reason: more than any of his other solo releases, The Rising of the Lights harks back to Drake’s time in Cardiacs musically while being inevitably informed by the grim reality of Tim Smith’s present condition. A natural successor to Briny Hooves in being a collection of lushly arranged, complex yet accessible piano songs, it also opens with two songs Drake wrote for the next, never-to-be-completed Sea Nymphs album. ‘Super Altar’ is distinctly Cardiacs-like: jaunty and upbeat, it barrels along like something Syd Barrett might have written if he’d joined ELO, while ‘Ant Trees’ recalls Drake’s long-ago adventures on the big ship Cardiacs lyrically as well as musically, albeit refracted through the work of Lewis Carroll: “Please remind me of the time that we were so divine, at the gates of dawn, a chessboard on the lawn… setting sail to hunt the snark, we thought it such a lark.”

Another song which feels almost like a direct tribute to Tim Smith is ‘Ornamental Hermit’, a cracked lament which opens with Drake confessing, “Of all the things you did for me, the one most splendid was to christen a place in me where I can be a most contented person.” One of the album’s highlights, it sounds like Peter Hammill riding a wheezing, broken-down carousel in a forever out-of-season, closed-up English seaside town, genuinely moving, odd and original. So too is the sorrowful ballad ‘In an Ideal World’, a comforting lullaby undercut by the knowledge that the world remains far from ideal, the swooning melody diving for hidden pearls on the dark sea bed.

If there’s a criticism to make, it’s that occasionally Drake’s precocity impresses rather than moves. The rustic Zappa-isms of ‘Mastodon’ or the light-operatic Captain Pugwash of ‘Ziegler’ leave me cold, while anyone who failed to succumb to Cardiacs’ sometimes oblique charms will probably not warm to the way ‘Wholly Holey’ swings jauntily from off-kilter knees-up to jazz-rock whimsy and back again, which is a shame, as the fidgety bombast conceals a touching meditation on the nature of love, and the album is a whole is rich in emotional and melodic generosity.

All is surely forgiven however for the glorious ‘Me Fish Bring’, which proves that Drake is best when he plays it almost straight, the faint surrealism of the title phrase/chorus actually providing an enriching oddness, conveying mysterious meaning and unnerving emotion in a way that familiar clichéd phrases can no longer do. Melancholy yet ultimately uplifting, this waltz-time piano ballad is deep and powerful, with a tidal pull to its movements. A haunting clarinet line counterpoints this celebration of life in the very shadow of death, providing healing balm for the soul. This song alone would make the album worthwhile, like discovering a wonderful oasis of breathtaking calm and beauty in the midst of a long jungle trek, all struggle and mosquito bites.

Drake found the phrase “the rising of the lights” in a Victorian medical journal. It’s generally believed to refer to a condition where the lungs or windpipe are obstructed, causing difficulty in breathing. Although Drake borrowed the term simply because he liked the sound of it, this is nevertheless an album about the struggle to live, to love, to express oneself and to find happiness in spite of the obstructions the world places in one’s path. For Drake it’s been a long, strange journey, from the early days of Cardiacs to the unexpected, bittersweet present. But whether you were along for the ride or not, this album contains songs to illuminate your life.

Collapse Board

Or: How I Stopped Worrying And Learnt To Love the Cardiacs.

A fair chunk of music that has been produced this year could be classified as music for people who don’t like music. A fair chunk of all pop music ever has been. You know the type. When I was a student everyone had to own Bob Marley’s Legend and Born In The USA. That was how it was. Produce the cassettes and you get to wear your keffiyeh down the uni bar. Not that some of it isn’t good – draw your own Venn diagrams here – but the music that gets sold at petrol stations has a particular flavour to it. I mean, if you’ve only bought a couple of albums in the last six months and you’ve picked from Fleet Foxes, Adele, Lady Gaga or Eddie Vedder and his faux-rustic, common man, back to basics ukefuckingleles, you’re consuming music in a very different way to someone who devours it for breakfast, lunch and tea, whose pulse beats faster at the thought of the filthy shouty racket that the best new band in town will make tonight and who can actually literally feel their mouth watering when they read enticing reviews of new releases (please tell me that’s not just me).

Everyone I’ve met who likes Cardiacs has LOVED music. Every single one. There is no such thing as a casual Cardiacs fan. They have the hunger on them. Music isn’t an optional extra, it’s the centre, the hub, the pivot around which everything else wheels. They get the shivers, they get the buzz. They don’t get Death Cab For Cutie from beside the till at BP before a long journey home to see the folks.

I’ve got to confess I’ve had my problems with Cardiacs in the past. Sometimes I’ve found their wackiness so teeth-gratingly irksome I’ve wanted to gnaw my feet off rather than listen to a minute more. It was so bloody wearisome, all that snickersnackery bouncing around. I wanted to put it under a blanket and sit on it. It had the same effect on me as Camel. Or Yes. Made me snarl. But recently I got roundly (and deservedly) berated on Facebook for dismissing a documentary on prog rock that someone had posted a link to. Pfft, not watching that, I smirked; it’s all codpieces and public school boys being pleased with themselves. Twattery that prizes ‘technical proficiency’, that chill passion-killer, above gawky inventiveness. Boy music. Clever-clever fancy footwork that does not ring my bell, no way, no how.

Which, behind the facetiousness, betrays a common-enough repulsion for anything that doesn’t conform to a class-conscious, post-punk directness; to an authenticity (whatever the fuck that means) which pays homage at the altar of down’n’dirty rock’n’roll by spurning silly time-signatures and mock-classical tomfoolery. Punk gobbed on music in 1977, so the story goes, and washed the streets clean of the degenerate, self-satisfied dross that the likes of ELP and Rush were wanking out over the album charts; freed us all to scorn the stomach-turning excesses of prog in favour of DIY attitude; got virtuosity stomped on by rough & ready’s size 12 DMs. Grrrwk: take that, velvet waistcoats! Sppplaf: take that, unnecessarily fiddly flute solo!

Well, the story is distorted rubbish. I was wrong about prog. Yes, it can easily be caricatured as indulgent wankery, but, as a savvy friend of mine said, it is actually as much about an attempt to find beauty as anything else. And that’s a quest worth following to the end of the line (even if it does involve whole symphony orchestras and unnerving facial hair). There’s nothing inherently pompous about being difficult; nothing gobworthy about ambition.

Cardiacs isn’t exactly prog, anyway. It’s been called pronk – a hybrid punk/prog beastie, combining prog’s proficiency with punk’s spikiness – which is going to have to do as a defining something, but there’s an anti-Cardiacs vibe at play in the press that is tied up with the anti-progism that’s been so evident in (un)critical thinking about music for the last few decades.

Nor is it boy music, not by any definition of the term that you care to make up on the spot. The audience for the Cardiacs-associated bands I saw last weekend was as gender-mixed (and enthusiastically engaged) a crowd as I have seen at a gig for years. Women musicians and fans abound in the Cardiacosphere. And a Cardiacs song which employs tricksy time-signatures that flick the rug out from under you just as you’re finding your feet in its patterns is going about the business of bending, breaking and re-making the rules in a contrary multi-coloured glory, not about proving how clever it is, as the most boyish of boy music seems intent on doing.

That story is wrong about punk rock, too; there was a good thick strand of fun and silliness to punk and its aftermath (think of Captain Sensible, if you must, but also of X-Ray Spex who were quite capable of being daft as well as furious) but somehow the Great Punk Creed that obliterated the cred of prog has managed to create a situation today where joyless fucks like Kings of Leon get lauded for their grittiness and the pogoing loons have been forgotten. How did worthiness win out over moshing? History is a peculiar business.

Of course Cardiacs’ music is clever. Of course it is fiddly. It is jagged. Silly. Playful. Roaringly scritchy. Stop-start-stop-go-go-GO widdliness to end all widdliness. It is, oh god, fun. It is jaunty. Jaunty. For fuck’s sake. A word that should make one and all wash their ears out with Pussy Galore. No leather kecks here. Nor cool, neither, not a drop of it. But what there is, is joy. And snatched beauty, so much better than the complacent here-it-is-on-a-plate kind. And songs that skitter hither and thither in wild abandon to make untidy girls in stompy boots and flowery dresses shake their hair on the dancefloor and laugh like maniacs. What the fuck was ever wrong with joy in pop music? When I stopped worrying about the whimsy and started feeling the noise, it all made sense. I got the scritchiness bug.

So to this: if you’ve never heard (of) Cardiacs and their tentacular side projects you have the chance to experience the record I am nominally reviewing here something like afresh. Virgin ears if not a virgin cultural perspective. William D Drake was a key member of Cardiacs for, oh, decades, and he has made a record this year with his new band which is as unlike Cults or Adele or Odd Future as is a giraffe. It’s not young, it’s not radical, it’s not provocative, it’s not innovative, it’s not ever going to be top of any pops, it’s never boring and it’s the very opposite of inoffensive (which isn’t, obviously, the same as being offensive) and it’s certainly not hip. In fact, you can be pretty sure that this is music is as unhip as anything you’ve ever encountered so far in your musical listening career.

Which is no bad thing. So let it go.

There’s an obvious connection in The Rising Of The Lights to a distinctively English strand of Sixties pop, to songs such as ‘See Emily Play’ or The Village Green Preservation Society; here are those jocular organs, that mock-pomposity and wry delight in an aesthetic that is now doubly-archaic (the support band at Drake’s recent gig, Crayola Lectern, which includes ex-Cardiacs man Jon Poole among its members, played the Cardiacs’ only cover, that of The Kinks’s ‘Suzannah’s Still Alive’; they also played Robert Wyatt’s sublime ‘Sea Song’, so do, as they say, the math).

Don’t expect very much in the way of yer actual straightforward songs; not a lot of beginnings, middles and ends here. These are unfurling carpet rides of pieces, littered with snatches of hornpipes and jigs, which make sudden switch-backs from tremendous thumping keyboard tunes to howlingly naff fairground skirls, which in turn are interrupted by choral interludes belted out in absurdly over-blown but glorious trembling harmonies. There’s no casual conforming to expectations of what makes a song, which is all to the good, if you can haul yourself over the perkiness stumbling block and stop hoping for the easy comfort of a returning chorus.

‘Wholly Holey’ skips and hops from the beginning in a roil of oompahpahs. It’s quite ridiculous, really. And, look, there’s the falsetto and harmonies nicked from Queen’s A Night At The Opera, all lawns and lemonade, as English as raised eyebrows and politely furrowed brows. The elegiac ‘In An Ideal World’ has a melody-line to bring spring to frozen earth, wound through waves of rippling piano by a hurdy-gurdy (well, yes, of course).

My taste leaning more towards the stately than the jolly, I found myself skipping ‘Zeigler’ (which makes an interlaced pattern of too-pretty reels and chunks of wilfully awkward discordant piano) third time round. But Drake writes tunes and lines to make you ache, most delightfully in ‘Me Fish Bring’, which is quite, quite lovely. It’s a pastoral sentiment bomb, deploying clarinets and honey-sweet melodies and images of wafting smoke and lambs grazing in fields to thump the hell out of cynical old (or young) hearts. Oof.

For all the layers of reference, all the self-conscious playing with musics past and paster still and the grandiose, tongues-both-in-and-out-of-cheek choral tub-thumping, the album roots itself nicely with Drake’s voice and lyrics: he’s got a perfectly decent but down-to-earth voice and sings of cups of tea and jacket potatoes and the nicknames lovers give each other. Homeliness in the midst of bombast. How very – again – English.

This is music that has utterly abandoned the urge to now-ness. If you don’t find that refreshing and admirable, then do feel free to go hang with Tyler and his hipster nemeses. I don’t know much about Captain Beefheart or the Penguin Café Orchestra, some of the more obvious benchmarks I probably should be leaning on here. I’m not all that up on the post-punk that informed Cardiacs’ jagged freneticism either. I stood in the queue for Drake’s gig yesterday and all around me clever beautiful women were talking to be-T-shirted men about King Crimson and Brian Eno. Seriously. I felt a bit dim. If you absolutely must have a contemporary comparison, think of Sufjan Steven’s utterly remarkable ‘You Are The Blood’, which has a similarily contrary attitude to genre and structure, pulls wholly disparate threads together yet does gorgeous so well. Course it doesn’t sound anything like this.

So never mind the context: this is a simple plea for you to pin your ears back and listen. An appeal on behalf of the Cardiacs party to put aside prejudices and engage with what these musicians are trying to do, to make. That’s what it’s all for, isn’t it, this wordy stuff? To coax you into sharing the thrill. And now I get it. I GET IT. This music here is about beauty and joy and delight. It cares not for fashion or convention or status. It’s for people who eat their music whole.

You’d hate it.

Prog Archives

To those in the know, William D. Drake’s songwriting credentials have never really been in doubt. His contributions to Cardiacs, The Sea Nymphs, North Sea Radio Orchestra and others, not to mention two exquisite solo albums of quirky, psychedelic prog-pop all attest to the fact that Mr Drake certainly knows how to write a decent tune. Sadly, none of these projects are anywhere close to being household names and Drake remains just another well-kept secret.

However, in yet another example of a theory I’ve espoused elsewhen on my blog, that could be about to change. For with his new album The Rising of the Lights, William D. Drake has taken a noticeable swerve towards the hallowed halls of Progressive Rock with a capital Prog, and (whether the mainstream music press likes it or not) that’s a move which is likely to net you a whole load of new fans. More than ever before Drake’s music invites comparisons to the likes of Robert Wyatt, Gryphon, Gentle Giant, (and naturally enough Cardiacs, The Sea Nymphs, NSRO etc.), whilst still remaining uniquely his own sound.

The Rising of the Lights retains everything about his previous album Briny Hooves which made it the accessible, sparkling, psychedelic wonder that it is whilst noticeably upping the ante when it comes to complicated twiddly bits, lengthy instrumental excursions and downright strangeness. The result is nothing short of a marvel; a patchwork quilt of rock, folk, chamber music and popular song, twisting and turning in a constant flurry of ideas and oozing breezy charm with every note. It’s a bundle of opposites, forever veering madly between catchy, hummable ditties and knotty complexity, between playful irony and soul-wrenching sincerity.

Mr Drake seems admirably unaware of musical fads and fashions, which gives the album a sense of complete timelessness. Songs like Super Altar, Wholly Holey and Ornamental Hermit reek of the music hall and oak-panelled libraries without ever fully letting go of those subtle psychedelic undertones, and just when you’re comfortably ensconced in a bit of woodwind-laden chamber music such as Song in the Key of Concrete in comes a fat, scuzzy synth to hurl you forward by several decades. It would be easy to accuse Drake of adding quirks for the sake of quirkiness, but the album’s more hushed, reflective moments, such as the achingly gorgeous Me Fish Bring, are thankfully free from such flights of musical fancy, and get by just fine with their unadorned, wayward melodies. For all its eccentricity, this is an accessible album, and a surprisingly moving one too.

It is a testament to this album’s consistently high standards that I’ve almost concluded this review without even mentioning three of my favourite tracks, namely the crackpot complexities of Gentle Giant-esque almost-instrumental The Mastodon, the time signature jumping surrealist pop gem Ant Trees, and the delightfully pompous album closer Homesweet Homestead Hideaway. Truthfully, I have yet to find a single dud or dull moment on this record, and that is a rare thing indeed. This is music to be cherished, to huddle up to on cold nights for warmth. I sincerely doubt I will encounter a finer album this year.

The Underground Of Happiness

Here’s what I know about William D. Drake. He used to be in English band Cardiacs. He’s obviously interested in English folk and medieval music – I have a hunch he enjoys silent film soundtracks too. His music is playful and quite surreal, but not at the expense of passion and energy. The instrumental track Ziegler starts like a Buster Keaton chase sequence (with twirling clarinet) before becoming very like the theme tune to (the fondly remembered Irish children’s tv programme) Wanderly Wagon. He’s a fantastic piano player, who sounds like he’d be right at home with jazz, classical, traditional or any other genre you’d like to throw at him. The song Ornamental hermit concerns the (presumably discontinued, although you never know) practice of wealthy English families keeping a hermit on their grounds. The title of the album refers to a disease found in 18th century London. Super altar is a medieval harpsichord melody glued together with a post-punk organ solo. On the other hand, In an ideal world is a plainly beautiful piano ballad. Overall, the album is warm, funny and hard to pin down. Not to worry, because above all it’s get-under-your-skin pop music. Learn to love it like a warm memory.

Freq

The Rising of the Lights is a record that feels exceptionally English – if someone said it was some hitherto unreleased Canterbury Scene opus, or some obscure Matching Mole side project, I’d likely not arch an eyebrow. It’s a record that’s indebted massively to Drake‘s tenure in Cardiacs, though a great deal less acerbic and more light and whimsical.

The first two tracks particularly shimmer in a Cardiac shadow – all rinky-dink piano and baffling time signatures. And there’s generally a real sense of quite a broad soup of influences on the music – there’s baroque flourishes, sarcastic/drunken lounge jazz sections, perhaps even a smidge of an oompah band thumbing lifts in the home counties. The lyrics too cover a fairly peculiar set of subjects – like sets of characters from childhood book, vicars and dragons pop up, puns about cups of tea (“he he he”).

Unfortunately, I’ve never had a very strong stomach for this sort of thing – the word ‘whimsy’ makes me cringe, and I get convulsions when a record is described as ‘surreal’ (as Drake’s press release does) There’s really nothing wrong with this record. It’s a lush recording, a lovely set of instruments all played tremendously well (I was particularly impressed with the clarinet’s tone, while wearing my jazz hat), a smart set of arrangements and some clearly well thought out, earnest but not cloying lyrics – I’ve just personally never got the hang of this sort of kitsch Victorian sort of view of England, all peculiar gnomes, eccentrics with curious maladies, tea sets and faint dismay. This record doesn’t really offend me, it’s just not (drumroll) my cup of tea. The only serious criticism I would level at it is that the hurdy-gurdy could be higher in the mix, which is flotsam as far as criticisms go.

I do feel bad for saying that though – I think this is definitely a record for fans of anything in the British psych vein – whether it’s early Pink Floyd (though this is far less druggy), Canterbury Scene, Robert Wyatt, Cardiacs…or any songwriting which is complex without being showy. Drake is quite the arranger, and clearly has the sort of intimacy with his piano that only gynaecologists could sympathise with. Mixing a sort of p-funk/hip-hop thing with baroque-esque piano lines (as on song in the key of concrete) is quite the feat. And while the playing is top-notch, there’s nary an ego in sight. Not a record for me then, but definitely one for those who’ve a taste for whimsy and smart arrangements.

Sounds XP

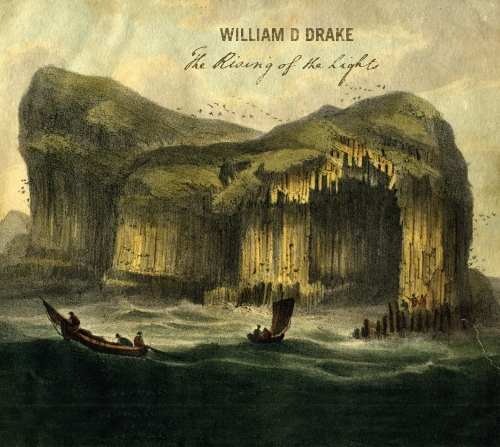

The old seascape cover painting and the album title (a contemporary description of an obscure cause of death in London in the 18th and 19th centuries) makes clear that Drake is a man inspired by the past and a pastoral view of the world. With songs like ‘Ornamental Hermit’ describing the practice of old English aristocratic families for maintaining hermits on their estate, and a range of instrumentation that includes hurdy gurdy and harmonium as well as melotron and mini-moog, there’s a sense of old ideas filtered though contemporary eyes, conjuring an image of William Blake collaborating with Robyn Hitchcock.

A couple of tracks originally written for his side project with Tim Smith sounds a little more Genesis-like with their difficult time signatures while the rest of the album is a paint-guide of different shades of English eccentricity, from the stomping prog-psych of ‘The Mastodon’ to the Morris dancing rhythms of instrumental ‘Ziegler’ and the fairy-folk of ‘Homesweet Homestead Hideaway’. The emotive ‘Me Fish Bring’ even makes me think of Kate Bush, a song where the lyrics make no sense but still fit the mood, and a perfect tone is set by a mournful clarinet and the melancholy male/female duet. Ideas just seem to pour forth and there are lovely melodies lurking within the tricksy time signatures, which make this fourth album perhaps a little difficult to get into on a first listen but reward the listener’s persistence.

The Organ

The Rising of The Lights might just be Mr Drake’s finest album yet. It certainly must be his most accessible. All English popular songs and countryside glow-worms, the title of The Rising Of The Lights may refer to a mysterious cause of death which plagued London during the 18th and 19th century, but this rising is William in the rudest of health.

Many of you will know William D Drake as a keyboard player in Cardiacs, and indeed The Rising of the Lights begins with two songs originating from the gentler offshoot of Cardiacs, The Sea Nymphs. No information here to hand as to whether Super Altar and Ant Trees have the work of Cardiacs frontman/composer Tim Smith actually in the recording, from before his illness, but they certainly sound like some of Smith and Drake’s intuitive collaborations. Both songs are brilliantly sparkling pop/ folk/ Edwardiana, shifting and curious, packed with musical detail that slips by easily – lighter and brighter than the rich sum of its parts. We may never see that lost Sea Nymphs album, now that Tim Smith is so ill and can neither play nor sing, so what a poignant joy to have these creations out in the world, and perfectly seamlessly joined in with Drake’s newer work.

There’s a satisfying balance between the deep and emotional ballad and the cheery strangeness across the album; the sorrow and sweetness of Ornamental Hermit and the very, very Gentle Giant super-Englishness of Wholly Holey, all suiting the soft, largely acoustic and analogue instrumentation: clarinet, harmonium, mellotron, hurdy-gurdy, mini-moog and sax. The driving piano riff and big harmonium chords of The Mastodon is as noisy as this album gets, right up to the storming ending: ‘Good Sir Thomas thought that he/ Had dis-covered the Mastodon’ (once again, that is rather Gentle Giant as played by Cardiacs!).

Drake’s voice is nicely listenable in its slightly cracked way on these songs, endearing and sometimes powerful, joined by various fine-voiced ‘so-called friends’ (unfortunately, we can’t find the details of who’s who just yet). The title track is a fine diversion, a slightly creepy, swamp jazz instrumental number that strives to replicate the sensation of that mysterious malady, those rising lights… and here comes the strangest pop hit of the century, Songs In The Key Of Concrete, a defiant stomp. In all there’s a faint hint of the echoes of those TV theme tunes we might have heard before we can remember, 50s and 60s Light Music… yet it’s all so fresh sounding. Fresh as a daisy.

And fun to lose yourself in: there’s Ziegler, a maddening sea shanty – maddening because it doesn’t sound like riding along green lanes in a curvy British Racing Green bus in the 1950s, it doesn’t sound like Captain Pugwash, or Vaughan Williams, or Gryphon… it should, but with it’s layers of clunking harmonium and home piano and sweet clarinet and brisk brushy drums and utter lack of self-conciousness it’s not quite like anything else. But it will slap a daft grin on your face.

All ends with an epic, unusual for Drake, a nine minute saga about a ‘sexy lonely dragon’, or someone like that, that climbs and soars from a very Sea Nymphs /Oliver Postgate soundtrack medley to overwhelming heights of emotion, wearing those Vaughan Williams wings.

The magic here is that for all the words like ‘whimsy’ and ‘cheery’ and ‘strange’ this is never, ever, ever cloying or forced or cheesy. This is deep and beautiful music, sometimes painfully beautiful. Real innocence, with no side, no hidden smirk, deeply honest – the strength in fragile things. This isn’t ‘eccentric’ music, this is delightful music, happy, sometime jolly, thingssometimes a folly, a chess board for a lawn. In An Idea World is just that, an ideal world, where everything is right, and there’s a time to act, a time to wait… In An Ideal World is perfectly beautiful, nether modern sounding or old, everything just right, tea in the correct cups, taken at the correct time. (Not to follow rules, but because it tasts nicer that way… maybe it’s just toy teacups). And then there’s the bits where things fly too close to the sun, like poor Icarus.

Mr William D Drake was once a small boy who lived in a house with a donated piano, but maybe there was also a harmonium, and maybe he’s still there, small feet pumping the pedals of the wheezy old thing, birdsong and the keys clicking, sending tunes half-heard ‘from the deep, dark past’ up dusty shafts of sunlight to the present day. These songs are no brassy knock-off imitations, or dead artifacts frozen behind museum glass, but magical, timeless things with the glowing depth of well-used mahogany. As much Blake as Drake, songs of innocence and experience.

Norman Records

Ex Cardiac and former professional David Mitchell lookalike William D Drake returns with another album of bonkers ever so English psychedelic pop. It upsets me on a daily basis about the ongoing illness of lead Cardiacs man the genius like Tim Smith who since 2008 has been severely ill following a stroke rendering the band out of action for the foreseeable future. For those missing his eccentric wordplay, fairground melodies and English whimsy this will work as a nice filler. Its odd that Drake didn’t contribute much more to his parent bands songwriting as this shows some lovely flourishes particularly the gorgeous ‘In an Ideal World’ which recalls Martin Newell’s brand of pastoral Englishness or XTC’s unsupassable ‘Apple Venus’ album. Elsewhere its roller-coaster melodies with nods to early Genesis, Stackridge, Madness, The Kinks and Of Montreal.

Losing Today

Being named after a Victorian malady seems about apt for this the latest melodic expedition captained by the goodly crooked and wired aural alchemist known as William D. Drake. ‘the rising of the lights’ comprised of 12 alluring suites is a feat of intricate craftsmanship that weaves upon a genre bending canvas an adept artistry that all at once shoehorns in moments of Cambridge folk, noir tweaked trims (the head bowed and mournful ‘ornamental hermit‘), beguiling baroque braids, skittish psych, Victoriana music hall, prog, Elizabethan motifs, opera, rainy afternoon bandstand squiggles (particular ‘Ziegler’ which should have admirers of both Vernon Elliott and the Trunk imprint slavering in swooning formations with its kooky 70’s children’s TV motifs) and more besides. Had Drake been born of another age he would have no doubt have been a dandified piper leading and heralding the arrival to town of some exotic circus of curiosities or else an impish courtyard jester. Like Legendary Pink Dot(er) Edward Ka Spell, Drake embraces the surreal and the abstract, by extracting the nectar of that most rarefied detailing of ye olde English eccentricity his creative mindset pens landscapes drawn and coloured in styles that cast favourable comparison with the likes of Syd Barrett, Vivian Stanshall and latterly And They Came from the Stars. Possessed of a more identifiable classically aired focus Drake navigates a musical odyssey that swells and sighs to an ornate tapestry stitched elegantly in the past and yet tenderly tweaked in the now, it’s a intrinsically and lushly informed melodic vocabulary that makes for a most rewarding spectacle of pristine harmonic perfection that has it located on an axis removed far from the fads, fashions and flirting fancies of current listening concerns. Equipped with an armoury of vintage instrumentation – a hurdy-gurdy, a melodica, a mellotron, a moog and a phillicorder among the symphonic strange sound sorties – ’the rising of the lights’ temptingly caresses with a richly laced romantic tug, neo classical suites smoulder aside the vampish twists of penny dreadful operas and lost shanty riddled with ghostly familiars.

Long time Cardiacs fans needn’t fear for he’s lost none of his impish persona for admittedly ‘the rising of the lights’ trades for the best part with a more sensitively sensual and beguiled kiss yet anything with signed the Drake handicraft wouldn’t be right if it omitted the odd moment of erratic schizoid psych / art / prog operettas – and so enter the fried demented time signatures of ’super altar’ and the lysergic soft psych music hall musings of ’ant trees’ both intended originally for Drake’s post Cardiacs collaboration (Sea Nymphs) with the ailing Tim Smith – and dare we forget mention of the skewed contortions of ’the mastodon’ which scored to an acutely raging wig flipped prog accent may well have the beards and beads of older VdGG and Crimson stalwarts falling out amid bouts of jaw gaping stunned admiration. The impish psych pop heads among you will do well to fast forward to ’wholly holey’ which indelibly weaves a deliriously dinky Purple Gang-esque persona playfully soldered with childlike kookiness and unhinged time signatures.

Best moment of the set though in our much humbled opinion is the touchingly shy eyed romance of ‘in an ideal world’ – cradled as it is by the demurring cortege of fulsomely longing string swells and swoons lushly set to an undulating landscape pepper corned by pastoral flurries, Brontean florets and Elizabethan garlands. though should any of you care to find yourselves still rooted on the fence wondering whether to jump in or not would do well to fast forward through the credits to unearth the epic parting shot ’homesweet homestead hideaway’ which in essence offers something of a hand held casual ramble into what is essentially an extended albeit crookedly crafted snapshot of this most becoming weirdly wonderfully adventure. File under precociously peculiar and perfect.

Crayola Lectern’s Ever Decreasing Circles

I must be careful as I have no interest in being a music critic but very occasionally I feel compelled to rejoice in certain records with a fervour, bordering on the evangelical, making me look to an outsider like a born-again, out to convert yet this is not for my secured place in the after-life, my salvation having already been achieved here on Earth, holding this thing in my hands.

This thing here in my hands is The Rising of the Lights, William D. Drake’s new album. The month of May has been a perfect time to ‘release’, it being the period in the calendar when flowers bloom and new life prospers. In fact, as I see it, William D. Drake has not released an album at all, rather he has had a baby. Lovingly written and played by all concerned, replete with all the joys and woes a life can muster, generous in so many ways, from the wealth of ideas to the tickling of the listener’s brain’s pleasure receptors, the enchantments, through to the packaging. It feels like a beautiful gift, lovingly wrapped and full of magic.

If artists, as are sometimes claimed, are mere vessels who capture the ghosts and vibrations from the ether, then the ether surrounding William D. Drake’s being must be supercharged with possibilities and great emotional depth, never overbearing, rather enticing, mesmerizing, leading me up the garden path to a place where the ornamental hermits and great adventurers dwell, alongside those other rare outsiders like William D. Drake himself who have the ability to write hugely accessible songs, but which still retain their intrinsic mystery, without cultivating a beard to prove the point (no slight intended, my dear beardy friends).

The “outsiderness,” I refer to is borne of a strong personal sense, unfettered by fashionable dictates, yet always looking forward, combining the old and new, a celebration of life, “overflowing with joy and with pain” without making a meal of it. It happens naturally, crafting out of Love’s own materials, he plays the notes he plays because it is coming from an inner place and to give it out to all us philistines is just plain kind of him. It’s a kindness he shares with Robert Wyatt – perhaps he over-estimates his potential audience due to a generosity of spirit which many lack.

The songs then, in a nutshell? Well, we have the playfulness of Super Altar, Ant Trees, Wholly Holey, Ziegler, Song In The Key Of Concrete – so unfair to lump them in together under such a trite heading, needless to say the playfulness is a mere foil for the wealth of ideas each of these songs possess. The gentle reassurances and soothings of Me Fish Bring, Laburnum and In An Ideal World, the gloriously exciting Mastodon with it’s amusing little lyrical moment, title track, The Rising Of The Lights whose luminescent bacteria stir from their dormancy with a seductive menace in preparation for an attack on the nervous system, full of mystery and danger and then there’s show-stopper, Homesweet Homestead Hideaway, which as the wonderful song subsides after the invocation, hypnotizes us to “go with the the flow” into dream, taking us together along tributaries and into a wide expanse where our souls let fly and there’s something of the end of a great Western to all this as the end credits roll and looking back over my shoulder I become aware how vast an inroad this album has made into my own subconscious.

That such redemption can be extricated from a circular piece of metal alloy will never cease to amaze me.

Sid Smith

Wacky as a hell but consistently brilliant with it, Drake’s fourth solo album is another dazzling, kaleidoscopic collection of songs in the key of E for eccentric. Recalling some of the manic energies generated during his period as a member of Cardiacs, it’s a strange parallel world where nothing is quite what it seems.

Repeated inspection of the fascinating layers of detail lovingly crafted into the record confirms a playful but intensely keen intelligence whose wry, melodic chamber pop offers a continual stream of surprising and intriguing turns on all 12 tracks.

Content-rich arrangements such as The Mastodon, overflowing with rippling themes, tumbling drums and prodding organ set inside a stirring march evoke Egg’s Germ Patrol or the strident insistency of John Greaves and Peter Blegvad’s Kew Rhone.

Populated with far-fetched tales, wild associative leaps and quick-fire word-play, there’s a guiding dream-like logic whose skewed wit is just as capable of confounding as it is of astounding.

Amidst quaintly tipsy intermissions and Oliver Postgate-on-steroids style instrumentals like Ziegler, piquant ballads such as the sublimely enigmatic, Me Fish Bring, suggest that within Drake’s exquisitely eclectic songbook there’s a yearning romanticism that is genuinely moving.

3Am

One of the most inspirational pieces of music writing from the past few years is Rob Young’s Electric Eden, an epic tome that charts the course of ‘Britain’s visionary music’. Taking William Blake as its spiritual mentor, it opens with the fin de siècle socialist salons at the Hammersmith house of William Morris, where WB Yeats, Oscar Wilde and George Bernard Shaw mingled with the youthful Gustav Holst and Ralph Vaughan Williams; through the quests of the latter and Cecil Sharp to record the country’s folk songs and sea shanties in the days before World War I; the reawakening of those dreams in the post-World War II folk revival spearheaded by Ewan MacColl; and how the urge, as Young puts it, ‘to get back to the garden’ reached a new golden dawn in the Sixties, with Nick Drake, Fairport Convention and The Incredible String Band. Thatcherism’s Season of the Witch might have brought those visions to bloody closure in a bean field near Stonehenge in 1985, concreting over the wilds of the British imagination with the creed of consumerism and selfishness; but Young hones in on certain artists who slipped through the cracks to deflect her curse, citing Kate Bush, Julian Cope, David Sylvian and Talk Talk, concluding optimistically that, ‘the song is never over’.

It is a book written with insight, empathy and – dare I say it – love. It was with great sadness that I put my copy down; and not just because I had come to the end of its vividly rendered and beautifully written pages. But because there was one chapter that seemed to be missing – regarding the music of Tim Smith and William D Drake. Maybe that’s not the fault of Young, who is both a diligent researcher and empathetic channeller of mystic Albion. It’s likely because that music is such a secret, even to a writer as open-minded and open-eared as him.

The spate of recent publicity around the plight of Cardiacs founder Smith, hospitalised for over two years after a double stroke and heart attack, and the subsequent Leader of the Starry Skies tribute album to raise money for his care, have been the most public attention this stricken genius has probably ever received. Cardiacs, and their musical progeny, have always been a clandestine sect, flowing beneath the surface of popular culture for three decades, like rivers under pavements. To the initiated, their songs of joy are the musical expression of Blake’s Visionary Imagination, the very epitome of ‘Electric Eden’.

Unfortunately, aside from the aforementioned Leader…, noviciates to the Cardiacs cause are currently unable to purchase much of either the back catalogue of the band, or their sublime side-projects, Sea Nymphs, Spratley’s Japs, OceanLandWorld and Mr & Mrs Smith & Mr Drake. However, a new release by William D Drake, a core collaborator of Smith’s in many of these bands, offers an introduction to this enchanted realm. The Rising of the Lights is an album brimming with unforced eccentricity that taps the leylines of British surrealism, the most Fortean corners of our forgotten history and the collective unconscious of a Seventies childhood.

The title itself perfectly evokes the entwined melancholy and euphoria of its contents, the wordplay at which Mr Drake proves as dextrous with as the fingertips he casts across the piano, harmonium, melodica, phillicorder, mellotron, mini-Moog and the Cardiacs’ patented ‘television organ’*. The Rising of the Lights suggests the dawn breaking. Yet the term came from an arcane medical journal. Aficionados of traditional carnivorous cookery will recognise the term ‘lights’ as referring to the lungs, and my contact at the Wellcome Library confirms that it describes a condition akin to diphtheria and asthma, also known as the croup.

“It was Miss Duggie Parker – she who sings and plays miniature tambourine and glockenspiel – who perchanced upon the said tome,” explains Mr Drake on the origins of the journal, discovered, appropriately enough, in that most mysterious and magical of cities, Venice. “To this day its howabouts remain her singular secret. Needless to say Mr James Larcombe – he of the hurdy gurdy – pounced upon the phrase ‘The Rising of the Lights’, and the three of us christened the album later in a small dimly-lit square in Venice over some local Prosecco.”

The track itself – a piano-led instrumental, augmented with spooked Theramin and strings that suggest the distant yowling of alley cats – conjures this noirish scene of conspiracy perfectly. It is a delightfully sinister number.

“Ironically, I have had real problems with my lungs,” Mr Drake reveals. “The only thing my GP could offer was a steroid inhaler, which took away the symptoms for a while, but only a while, then began to make me feel even worse than before. Have sought quack after quack – one says to breathe deeply, another says to take small, shallow breaths. I’m currently trying the Buteyko breathing method, whatever that is.”

‘The Rising of the Lights’ is an 18th century term and Mr Drake returns to that era for the subject matter of another of the album’s standout songs, ‘Ornamental Hermit’– a fashionable practise for rich landowners to install faux mystics to live in their grounds in order to amuse themselves and their guests. This gem of forgotten history was gleaned from English Eccentrics by that great defender of the strange, Dame Edith Sitwell, who defined the condition of eccentricity as “a kind of innocent pride” and is precisely the sort of person you could imagine bumping into down the front at a WDD gig. Does Mr Drake actively seek out oddities and curiosities – or do they have a way of finding him?

“A bit of both. I am at my happiest when rummaging around old junk shops full of precious rubbish – and I do occasionally find something amazing. I think I compose in a similar way – searching for melodies, chords that have an odd life all their own. I like ugly vases. I buy them then hide them away. I’ve always liked ornaments – it’s always interesting to see what someone has on their mantelpiece. They do also have a way of finding me too.”

‘Ornamental Hermit’ is a bittersweet song, which perfectly evokes a solitary soul creeping through crumbling formal gardens at twilight, ‘overflowing with joy and pain’ inside. A similar, beautiful melancholy pervades ‘Me Fish Bring’, with it’s misty cello and piano that imitates the babbling of a brook. There is a heightened visual sense to this music – to me it lies somewhere between painting and cinema, like the fairytale quality of Charles Laughton’s moonlit masterpiece Night of the Hunter. It’s often said that music is the third dimension of cinema but The Rising of the Lights works the opposite way round, allowing the listener to start rolling visuals in response to what is heard. Does Mr Drake have images in mind before he starts composing the music; or does the music create the images?

“It’s all a bit of a mystery,” he says, “and within that mystery is colour and shape and smell and taste – and the other one. Voices and images before one falls asleep. Many of my pieces have a long gestation period – can easily be twenty years – during which time they will attract a nostalgia or sentimentality from the period that they were spawned. And creatively they are not finished until the very last millisecond of recording.”

Besides the formidable Dame Edith, are there specific authors who have had an impact on his wistfully evocative, semi-surrealistic lyrics?

“I like Dylan Thomas’s tumbling poems, so full of humour and love and warmth,” he considers. “I like Barbara Pym’s novels set in English villages, where seething passions, often unrequited, penetrate the sleepy surface. I like Samuel Beckett’s short stories, particularly First Love, which is so peculiar that it comes close to actually reflecting life accurately. I like WB Yeats’s soft and serene poetry. I like Kurt Vonnegut’s absurd realism. Iris Murdoch’s mystery and mysticism. I like William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience. They’ve all influenced me in their ways.”

There is a bestiary of fantastic creatures on the album – from great dragons and mastodons to tiny ants and fish, whose peculiar characteristics are fashioned in comical musical ways, that chime with long-lost childhood memories, of programmes like Tales From the Riverbank, Mr Benn and the oeuvre of Oliver Postgate and Peter Firmin. There have always been plenty of fish, horses, dogs and other beasts in the songs of the Cardiacs’ extended family and I wonder if Mr Drake is drawn back to this kind of imagery by similar recollections?

“Many of my childhood memories are of drawing and painting, and the theme was nearly always creatures, both real and imaginary,” he says. “I was keen on Beatrix Potter, Walt Disney and Tales From the Riverbank. Animal Magic was a favourite programme – do you remember the theme tune? And Johnny Morris speaking like a giraffe?”

All of these themes within his work seem to add up to an on-going exploration into the landscape of Albion and the English eccentric soul, almost a mystical musical quest, similar in its purpose to that of Sharp and Vaughan Williams nearly a century ago, riding their bicycles across country and coast to record the old stories and songs before they disappeared into the aether. The tramping of Alfred Watkins’ The Old Straight Track that seems present in the resultant symphonies of Vaughan Williams, and those of Edward Elgar and George Butterworth. I hope I am not being too wildly pretentious here, as there is obviously a huge amount of humour and appreciation of the ridiculous in the mix too, but then again, that is all part of the equation, isn’t it?

“I do have a strong sense of Englishness — and my music is a kind of quest — a relentless one, I am a hopeless addict,” Mr Drake admits. “Absurdity is vital in helping me through my life — as is a good cream tea. I do feel a connection with the three composers you mention, especially Elgar and Vaughan Williams. Even if I was never to hear their music again, the thought of what they achieved musically is fodder for the imagination.”

Louder Than Bombs

Keyboard maestro and ex-Cardiacs tunesmith WILLIAM D. DRAKE writes songs that are timeless, bold and beautiful. MR SPENCER admires the musical scenery…

Imagine, if you will, a world in which arguably the most creative songwriting team of a generation remains on friendly terms after calling time on a radical and revered musical partnership.

In this ideal world, the brilliant, mould-breaking band they had created would still exist, with its visionary founder at the helm. Meanwhile his former songwriting partner, having left to follow fresh musical pursuits, would go on to produce increasingly free-spirited and spicey sounds, and their creative collaborations would continue.

And imagine this. What if the music produced by both artists, post-separation, remained remarkable?

In the case of Cardiacs’ Tim Smith and William D Drake – whose kaleidoscopic legacy has been compared to that of Lennon and McCartney’s extraordinary but sadly fragmented Beatles partnership – the above scenario is real.

“I’ve always felt free musically,” says softly-spoken keyboard maestro Drake, currently the subject of glowing reviews with his new album, The Rising Of The Lights, “so it was a relief to meet such a kindred spirit in Tim.”

Mr Drake, as his admirers tend to refer to him, was born to rock. Or more correctly, he was born to play stately, self-penned music on a variety of keyboard instruments including Hammond organ, Fender Rhodes electric piano, harmonium, Mellotron, synthesizer and, most magically of all, the ‘television organ’.

The latter device he accidentally invented himself, according to legend, while attempting to repair a faulty television set owned by Cardiacs. The story goes that after he’d finished tinkering with the set it produced a sound so beautiful that it made the band’s kind-hearted and possibly mythical corporate consultant Miss Swift cry. The television organ’s fragile melodic quiver remains an instantly recognisable element in Drake’s warmly creaky, folk-tinged music to this day.

During the eight years Drake spent in Cardiacs – nowadays increasingly acknowledged as an important and influential band – his onstage ‘character’ often seemed happy but also bewildered to find himself playing in such off-beat circumstances. Did he ever feel like an innocent abroad during this period?

“I’ve spent all my life feeling like an innocent abroad,” he says. “Even when I go to the greengrocers. That’s why I never go on holiday – it’s far too traumatic.”

MUSIC WAS central to life in the young Drake’s family home. Born in Stock, Essex, he was barely toddling when he developed a close relationship with a handy child-sized harmonium, and later began to learn his trade on a neighbour’s loaned piano. His mother and grandmother encouraged him to develop his formative talents by teaching him to play the popular waltz Chopsticks, and sustained this support throughout his classical piano training, which continued until he was 18.

“It was just right – ideal,” he remembers, “because it shaped my life. I became so addicted to harmoniums and pianos that nothing has been able to drag me away from them ever since.”

Were you immersed in music from the word go?

“I had piano lessons quite early on, when I was about five, with my teacher Hilary Tudor. My grandmother and mother both taught me duets.”

Did they have classical backgrounds?

“My grandmother was a student for a year at the Royal Academy of Music, before my grandfather whisked her off to get married at the tender age of 18.”

Later on, when you were being trained to play classical piano, where did this happen?

“I had piano lessons at school, first with Elsie Pearce and later with Rhona Parkinson. I went to a boarding-school in Broadstairs when I was just seven, where I was subjected to solitary confinement in various poky rooms with pianos and told: PRACTISE OR ELSE! I thanked them for it in the end.”

As he entered his teenage years, Drake’s formally shaped musical musings were bumped into less conventional territory when he developed a passion for the pioneering pop of the Beatles and David Bowie. Eventually, when he was 21, he played a gig with his first band Honour Our Trumpet at the Grey Horse in Kingston, Surrey.

The sound engineer that night was Tim Smith, leader of Cardiacs, a local band with a liking for punky but intricately detailed compositions. Smith was so impressed by Drake’s keyboard skills that he immediately wrote out a complicated musical score and challenged him to play it. The tune – which would later form part of the song Hope Day – was fiendishly tricky, but Drake performed it with ease. After this his fate was sealed, and in 1983, the nimble-fingered pianist teamed up with Smith’s fast-evolving twisty-pop outfit.

Was Drake surprised, following his traditional musical education, to find himself plastered in make up, playing swirly, spectacular music with Cardiacs?

“I wouldn’t really say that my ‘education’ was conventional,” he gently contends. “And I could not have found a band to suit me better in a billion billion billion years of searching this big ol’ universe!”

What did your mother and grandmother make of you hooking up with Cardiacs? Were they alarmed by the onstage oddness?

“My grandmother died when I was seven. My mother and father used to come to many of the gigs, they seemed to fit in rather well with the rest of the audience.”

Did their classically-attuned ears help them to appreciate the music?

“Well, my mother doesn’t just like classical music. She used to listen to Trini Lopez and The Tijuana Brass when I was growing up. I think too much is made of classical musicianship in the rock or pop world. Many people are taught in a classical way – it’s the standard way to teach – nothing particularly unusual or amazing about that.

“My parents came to lots of gigs. My mother would bring a shooting stick and sit by the sound engineer, which was often where the onslaught of sonic debris was paramount.”

Having received a formal musical education, when you joined Cardiacs were you forced to unlearn much of what you’d been taught?

“No, because I didn’t play just classical music. There was soft pop, country dance, polka, rock, light opera, curly wurly, jazz, and everything in between.”

***

WHEN DRAKE joined Cardiacs he was a godsend for the creatively fizzing Tim Smith, who was now able to write devilishly complex parts for keyboards as well as for guitars, allowing his already wide musical horizons to expand further as the band’s songs were increasingly adorned by Drake’s dazzling classical flourishes.

Drake’s first gig as a Cardiac was at London’s Marquee Club supporting Seventies festival circuit survivors Here & Now, but Smith’s opinion-dividing troupe toured solidly and soon began to attract a loyal following hooked by their legendarily spectacular gigs and the epic tunes being penned by what was developing into a remarkable songwriting partnership.

Many of Cardiacs’ most lovingly layered, emotionally potent and poetic songs emerged during Drake’s time in the band. Among these were I Hold My Love In My Arms (which featured music he’d written when he was 15), The Duck And Roger The Horse and Blind In Safety And Leafy In Love.

One of the songs he co-wrote, The Everso Closely Guarded Line, begins with a ripple of warm piano that evokes, within a few seconds, the polished-wood atmosphere of school assemblies, a heady mixture of fear and limitless possibilities – was there a kind of nostalgia in Drake’s musical mix even then?

“I wrote the opening bars of Everso Closely Guarded Line fresh from having spent eleven years of my life at boarding-school,” he recalls. “So if ‘nostalgia’ means homesick – yes, there was a bit of that, and it would perhaps be reflected in my composition.”

Did you and Tim cross-pollinate musically – to the benefit of you both?

“Yes, like a couple of busy bees. In the songs that we co-wrote we brought in both complementary and complimentary sound odour.”

How much lyrical input did you have?

“Tim wrote all Cardiacs lyrics whilst I was in the band, I think. But I did come up with the word ‘brown’ for the song title Burn Your House Brown.”

In addition to playing and recording with Cardiacs, Drake also worked with Smith and his then-wife Sarah Smith on the Mr and Mrs Smith and Mr Drake side-project. Using this name and later as Sea Nymphs, the trio released two albums containing many of Drake’s most endearingly odd and sepia-tinted songs, including The Collar, Dog Eat Spine, Summer Is A Coming In and the glorious From My Piano To Mr Drake, which he performs live to this day.

***

IN 1991 Drake was consumed by a hunger for fresh challenges and decided to leave Cardiacs, but he continued to work with Tim Smith as part of Sea Nymphs as well as releasing his debut solo album William D. Drake – produced by Smith – on his former bandmate’s label, while also forming his own bands Nervous and Lake Of Puppies and touring with country-rockers Wood.

Sea Nymphs were reactivated at the end of the Nineties and even recorded a session for John Peel, although this had to be achieved using semi-covert techniques, due to Peel’s producer John Walters’ intense dislike of Cardiacs. Fortunately, Walters was unaware of his guests’ individual identities at the time and the session was completed successfully.

“We were hastened in through the tradesman’s entrance,” Drake recalls. “We did our bit then scurried off like Flopsy, Mopsy and Cottontail!”

Talking of Sea Nymphs, I’ve heard that unreleased recordings exist – is this true?

“Yes,” Drake confirms in positive news for fans starved of new material since Tim Smith was tragically felled by two strokes and a heart attack in 2008. “There’s enough stuff for at least one, if not two, albums.”

***

EXPLORING WILLIAM D. Drake’s repertoire sometimes feels like browsing the dusty, well-worn but much-loved offerings in a tucked away book shop; a treasure trove of little-known delights waiting to be discovered and enjoyed.

Is the charming and modest Mr Drake content with his current low-key-but-critically-acclaimed level of success.

“I will be happy when I can make a living from my music,” he says, “as I’d prefer not to live in a garret forever.”

Fortunately, in recent years, Drake has increasingly attracted positive attention as a solo artist, releasing two acclaimed albums in 2007, Briny Hooves – featuring the exquisite The Fountains Smoke and Serendipity Doodah – and its instrumental companion album Yew’s Paw, while also working with North Sea Radio Orchestra, a similarly admired chamber music ensemble whose line-up features two of Drake’s former colleagues from Lake Of Puppies.

However, 2011 looks set to be his most successful year so far. In addition to contributing a beautiful version of Tim Smith’s song Savour to the album Leader Of The Starry Skies – a compilation released to raise funds for Smith’s continuing treatment and recovery – Drake’s enthusiastically received fourth solo album, The Rising Of The Lights, is introducing Drake’s virtuoso talents to an increasingly receptive world as well as reviving the contemporary medical term for a long-forgotten illness which plagued London in the 18th and 19th centuries. “The record was named after an ailment of the lungs,” confirms Drake, “which ironically I have been suffering from ever since.”

Despite its surreptitiously sinister title, The Rising Of The Lights is a gorgeous, uplifting album with a rich, live-sounding sonic landscape providing a perfect backdrop to songs which pay homage to fields, rivers, breezy valleys and bleating lambs, all sprouting forth from Drake’s piano, mellotron and harmonium along with Nicola Baigent’s clarinet and James Larcombe’s wheezy hurdy gurdy. Additional acoustic and slide guitar heroics are provided by Richard Larcombe and ex-Cardiac Mark Cawthra. Oh, and ‘catsong’ is supplied by two actual purring pets.

Lovingly gift-wrapped in a sleeve adorned with artwork from a leatherbound 19th century “book with magic leaves” inherited by Drake’s mum, the record both looks and sounds like a treat. It brims with brilliant tunes and mad-but-it-works ideas, from galloping opener Super Altar, originally written for Sea Nymphs, to Wholly Holey – which your milkman would whistle if he was lucky enough to hear it – and Ant Trees, which starts at a jaunty pace but climbs to a gasping television organ climax.

It is elsewhere though, during the album’s more pastoral moments, that Drake knocks us for six. In An Ideal World and Me Fish Bring drift like boats at sea on a warm night, Drake’s slightly cracked, brink-of-tears vocals at their loveliest on the latter as he sings his prayer to nature’s wonders (“The sun it shine on everyone, be happy, be happy…”) accompanied by Dug Parker, her voice floating over some of the sweetest piano Drake has ever played.

Ornamental Hermit – “overflowing with joy and with pain” – nails the sublime sadness present in so much of Drake’s work as our hero’s fingers glide across his keyboard to produce notes that splash like summer rain. Pop piano hasn’t sounded this good since Mike Garson tinkled the ivories on Bowie’s Aladdin Sane, and that’s saying something.

The album closes with Homesweet Homestead Hideaway…, an elongated number that celebrates “the purring of the landscape, so bold and calm and true,” unfurling over several sections culminating in a dizzying, drawn-out swirl of shimmering flutes – a breathtaking achievement that stirs memories of a certain similarly majestic Cardiacs song.

“It is definitely a relative of Everso Closely Guarded Line,” says Drake. “Perhaps a much younger sibling that arrives somewhat unexpectedly to all concerned. It’s one of the more recent songs written for this album – The Mastodon, for instance, is at least 20 years old.

“Some pieces can take so long to see the light of day that by the time they are released it’s like children growing up and leaving home.”

Early in 2007, when Briny Hooves and Yew’s Paw were simultaneously released, Drake expressed a wish to renew his working relationship with Tim Smith (“he’s just finished building a huge studio,” he said at the time, “so I’d like to record there at some point”). Heartbreakingly, while Smith remains ill, this ambition seems unlikely to be fulfilled in the immediate future.

Is Drake still striving, in Smith’s enforced absence, for the ‘pungency of sound’ they created together in Cardiacs?

“Each song has its own individual smell. That’s why recording is such fun, to strive to create that particular smell.”

Does the drama of crashing waves appeal to you, all that briney sound odour?

“I do have a romantic notion of the sea, and I like to spend as much time by it as possible, which is not nearly enough.”

Your songs are often melancholy and yet so many of them also make the heart soar. Do you agree with the theory that sad chords are often the most uplifting?

“A sad chord all on his tod can sound dull and unilluminative. However place him between two happies and suddenly there’s all sorts of cats being let out of bags.

“I’m very fond of Robert Wyatt and his music,” he adds. “I like to water some of my songs with tears, it helps them to grow.”

***

DRAKE’S FONDNESS for discovering faded but exquisite musical artefacts extends to his passion for rummaging through junk shops for vases of all shapes and sizes. As he points out, taste is a very personal thing.

“Ugliness is in the eye of the beholder,” he says. “I collect vases that lots of people might say are ugly, but I think are damned fine.”

Does he like the idea of a musical continuity passing down the centuries?

“I do, and the history of music should be taught to everybody in their formative years.”

As a piano teacher himself during daylight hours – working “all over the place, and from home too” – Drake knows his stuff.

“There can be appetising music in most forms – a bit like food,” he says wisely. “It all depends on the restaurant.”

Are your students aware of your own musical accomplishments, both solo and with Cardiacs, Sea Nymphs and all the rest?

“Some are.”

Do you strive to stay within a standard musical framework in your lessons?

“When you’re teaching anything you have to keep within fairly conventional parameters, but I encourage everyone to make up their own music.

“Any sort of snobbery is a turn-off,” he continues. “But musical taste is an important thing to cultivate, there’s no use pretending you like something when you don’t.

“Personally I love Cuban music. I enjoy its sweet and grand sadness, and its elegant dance rhythms. Plus it reminds me of tequila slammers, my favourite tipple.”

Is there a perfectionism in the music you make, or is it more a quest for a kind of flawless imperfection?

“I do like to get the sound as gorgeous and beautiful as possible. And I am constantly making last-minute amendments, luckily my band are long-suffering. And what a fabulous bunch they are.”

***

WORDS HAVE always played a key role in Drake’s compositions, adding an additional layer of mystery to his sometimes graceful, often stirring, always absorbing melodies. In the case of Laburnum, from his new album, the lyrics are affectionately swiped from James Joyce. Does he delight in placing unlikely texts alongside terrific tunes?

“Lyrics will always be important to me, as I will always write songs,” he says. “I enjoy setting a good poem, particularly an old-fashioned one. I remember coming across the poem Sweet Peace by Samuel Speed, and feeling I just had to set it [this became the song Sweet Peace on Briny Hooves]. I couldn’t find any information about him anywhere, all I knew was that it came from a collection called Prison Piety.

“I buy books regularly. I can often be spied in one of the secondhand emporiums in Charing Cross Road. Unread books burst my shelves, but they’ll be read one day. I have a bookworm gene, it just hasn’t manifested yet.”

Drake tells me he often plays musical “tricks” on himself to keep his work fresh. Would he worry if his melodic creations lost what his biography describes as his ‘flagrant disregard for the division of modern and ancient’? I’m thinking of the way the televison organ drifts in and out during otherwise relatively conventional songs, or the audibly clattering keyboard on Poor John from the album William D. Drake; or the gloriously catchy Summer Is A Coming In, which compels the listener to attempt to sing along to its baffling, apparently olde English lyrics…

“I don’t think of my music as being odd,” Drake points out. “I just write what I feel like writing. The television organ and harmonium always add heart and warmth, like old friends.”

So, where did those Summer Is A Coming In lyrics come from?

“I found them in an old book, they were written in the thirteenth century. I knew nothing of the film The Wicker Man, which I since discovered has its own setting of the song. We altered the words ‘cuckoo, cuckoo’ because we looked like twats when we sang them. ‘Dodo, dodo’ seemed more fitting.”

Finally, can you explain to me – how the hell do you play the television organ?

“If you’d like some lessons, then you would be most welcome. But you’ll have to come to mine, as she’s not an easy old girl to carry around.”

* William D. Drake’s new album The Rising Of The Lights is out now on Onomatopoeia Records. Leader Of The Starry Skies is available now from all good record shops and online (in all formats) from the Genepool All money raised will go to Tim Smith to support his continuing care.